India-born scientist Ramesh Raskar was awarded $ 500,000, one of the world’s largest single cash awards for invention, for his path breaking work on an ultra-fast imaging camera that can see around corners, eyecare solutions and a camera that can read closed books.

The Lemelson-MIT prize, given by the School of Engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), honours U.S. inventors working on science and technology projects for the betterment of the world.

Ramesh, 46, who is originally from Nasik, is an imaging scientist and Associate Professor at MIT.

In addition to working on low-cost eye-care solutions for the developing world and a camera that allows users to read pages of a book without opening the cover, Ramesh is the co-inventor of radical imaging solutions including femto-photography — an ultra-fast imaging system that can see around corners.

“Ramesh’s femto-photography work not only has the potential to transform industries ranging from internal medicine to transportation safety, it is also helping to inspire a new generation of inventors to tackle the biggest problems of our time,” said Dorothy Lemelson, chair of the Lemelson Foundation, in a statement.

Ramesh plans to use a portion of the Lemelson-MIT Prize money to launch a new effort using peer-to-peer invention platforms that offer new approaches for helping young people in multiple countries to co-invent in a collaborative way, the statement read.

Despite living in the US, Ramesh has stayed connected with his roots in India through his work. During the Kumbh Mela in Nasik in 2015, he collaborated with other scientists to launch ‘Kumbhathons’ (special innovation camps) to develop ideas for the evolution of smart cities in India. This included exploring innovative solutions in the areas of housing, sanitation and transportation of pilgrims at the festival.

Similar Articles

Balkissa Chaibou dreamed of becoming a doctor, but when she was 12 she was shocked to learn she had been promised as a bride to her cousin. She decided to fight for her rights – even if that meant taking her own family to court.

“I came from school at around 18:00, and Mum called me,” Balkissa Chaibou recalls.

“She pointed to a group of visitors and said of one of them, ‘He is the one who will marry you.’

“I thought she was joking. And she told me, ‘Go unbraid, and wash your hair.’ That is when I realised she was serious.”

The young girl from Niger had always been ambitious.

“When I was little, I was dreaming of becoming a doctor. Take care of people, wear the white coat. Help people,” she says.

Marriage to her cousin, who had arrived with his father from neighbouring Nigeria, would make this impossible.

“They said if you marry him you won’t be able to study any more. For me my passion is studying. I really like to study. That’s when I realised that my relationship with him wouldn’t work well.”

Niger’s tradition of marrying its girls young – it has the highest rate of child marriage in the world – is partly rooted in its grinding poverty.

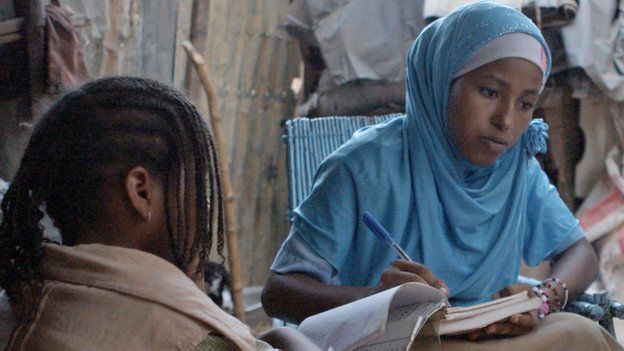

Chaibou, with her sister, says that she loves to study

“The dynamic works in this way: I have lots of children, and if I can marry off one child that is one child less that I have to feed,” explains Monique Clesca, the United Nations Population Fund’s representative in Niger.

Balkissa Chaibou’s parents had five daughters, so from their perspective marrying her to her cousin may have made economic sense.

But another reason for the tradition of early marriage in Niger is the belief that it reduces the risk of pregnancy outside wedlock.

“Nowadays some children are not well brought up,” says Hadiza Almahamoud, Chaibou’s mother. “If they are not married off at an early age, they can bring shame to the family.”

Chaibou continued to work hard at school, waking at 03:00 to study, but as she got older the looming marriage with her cousin became a distraction.

Then, one day when she was 16, the bride price, suitcases and a wedding outfit arrived.

“I felt pain inside of me, it really broke my heart,” says Chaibou. “Because I see that I am fighting to fulfil myself, and these people will be an obstacle to my evolution.”

She plucked up the courage to try to get out of the marriage after getting her junior high school diploma. “I told myself that I can try to pull myself together, see how I can escape this situation.”

Her mother understood her objection to the marriage but didn’t have the status, as a woman, to help her.

So Chaibou approached her father, suggesting that as a compromise she could marry but only see her husband in the holidays until she had completed her Baccalaureate.

But the tradition of the Tuareg – the ethnic group to which Chaibou belongs – is that the older brother has power over the children of his younger siblings.

Since Chaibou’s uncle – the father of her fiance – was older, her father dared not go against his wishes and preparations for a wedding continued.

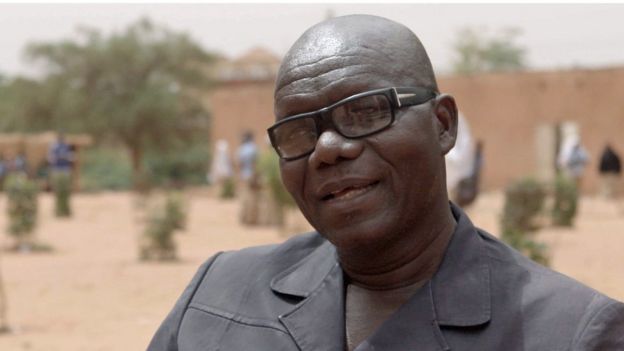

In desperation Chaibou asked her school principal, Moumouni Harouna, for help.

He referred her to an NGO called the Centre for Judicial Assistance and Civic Action, which took legal action against her father and uncle for forcing her into a marriage she did not want.

Once in court, Chaibou’s uncle denied the accusation, she says, and claimed it had all been a misunderstanding, so the case was dropped.

But once she got home, her uncle threatened to kill her.

“He said that even if he had to wrap me up – even if he had to wrap me up in a body bag – I would go [to Nigeria],” says Chaibou.

She was forced to take refuge in a women’s shelter.

Her school principal put her in touch with an NGO that could advise her

“The first night spent here I didn’t sleep well,” she says. “I was thinking too much about my parents, about the situation they were in, especially with the anger of my uncle. I was sure he would insult them and threaten them, so I didn’t have a clear mind.”

But faced with the threat of jail, the wedding party returned to Nigeria and after a week Chaibou was able to go home.

“When I put on my school uniform… I felt like my life was renewed. As if it was a new beginning,” she says, describing the day she started college.

Her mother says that she and her husband have now changed their views on forced marriage.

“We are finished with [it] in this family. We are scared of it,” she says. “If a girl grows up she can choose her husband. We can’t do it.”

Mariama Moussa – president of the shelter Chaibou took refuge in – says domestic violence is a serious problem in Niger and that forced marriage is one of the root causes.

“When you force them, as a result there is a succession of violence that they can suffer in their home,” she says. “There is physical violence, psychological violence… When the husband cannot tolerate her any more, he can hit her, or make her leave, even in pregnancy.”

Chaibou is aware that now she has won her freedom it is important for her to succeed in her studies and repay her family’s sacrifice.

“I know my family’s hope is on my shoulders. Everyone counts on me. Everyone has their eyes on me,” she says.

Now 19, she campaigns for other girls to follow her example and say “no” to forced marriage. She visits schools and has spoken to tribal chiefs about the issue.

She has also spoken at a UN summit on reducing maternal mortality, a phenomenon linked to early marriage.

“Before [the age of] 15 the body is not ready to have a child,” says Clesca.

“About 34% of adolescent deaths in Niger are maternal mortality, which gives you a sense of the problem.

“It is important for the Balkissas of this world to stand up because it shows the other girls that ‘Hey, I can do this.’

“And yes we have seen a ripple effect. One girl says no and others are crowding around her [saying] ‘What did you do? I mean, why did you say no?'”

Balkissa Chaibou is getting closer to becoming a doctor. She passed her International Baccalaureate and is currently at medical school.

“I’m not saying don’t marry,” she tells one group of schoolgirls.

“But choose the right moment to do so. The advice I have for you is to fight – study with all your might. I know studying isn’t easy but you must force yourself because those studies are your only hope.”

Article and Image source – bbc.com